Ghostly Abstractions

‘Ghosting’: ending a relationship through the withdrawal of all communication. Shutting off. Going hermetic. ‘Ghosting’: the appearance of a ‘ghost’ or secondary image on a screen, often in the background. So what happens if that background wants to come into the foreground? Who gets to be foregrounded, and who not, is a political decision. Or is it something beyond decision? The philosopher Henri Bergson connects it firstly with memory: ‘when a memory reappears in consciousness, it produces on us the effect of a ghost whose mysterious apparition must be explained by special causes. In truth, the adherence of this memory to our present condition is exactly comparable 'to the adherence of unperceived objects to those objects which we perceive.’ This ghostly ‘adherence of unperceived objects’ is what (1) troubles us. Twelve years later Bergson will revise this account of memory with the idea of a ‘Memory of the Present’ to explain ‘false recognition’ (or déjà vu): what we feel to be a relived moment is simply a doubled moment – one that is perceived and remembered at the same time. Doubled. Why this effect occurs, the glitch in perception-memory, is never explained. Cognate notions such as the ‘uncanny’, ‘defamiliarisation’, even ‘re-enchantment’ – all of which double the moment with its own ghost or secondary-image – might be invoked. Could an artist create a visual artefact with family resemblances to these – imagery that ‘is familiar and unfamiliar at the same time’?(2)

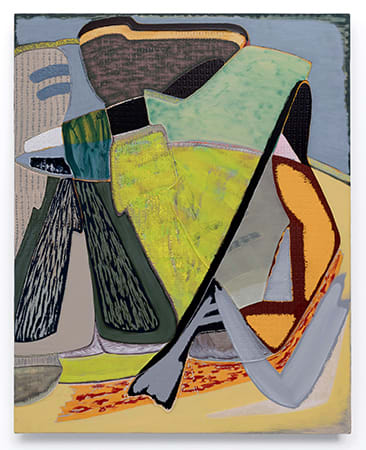

Follow the instruction: ‘Stare at something, then close your eyes – see the after-image’. Perhaps this is too (3) voluntarist – too much in the gift of the seer? What if the art-object itself created the effect, doubled itself in front of us? It is not that the painting looks back, or resists our seeing, but that our looking is doubled through ‘its’ looking, at the same time. Michel Henry’s reading of Kandinsky’s abstractions turns to Life as auto-affect: ‘the abstract content of art’ simply is the ‘pathos of force that produces this graphism’, it is the ‘pathetic diversity of life’. Self-feeling of (4) life. But there is another way: the immanence of memory and perception, as Magalie Guérin writes: ‘Abstraction seems related to memory somehow; a felt memory as opposed to an image memory perhaps. […] How does abstraction relate to time?’ Answer: through repetition. These works ‘started as twins but ended as distant cousins.(5)

Still, same family’. She continues, elsewhere, as follows: ‘In my latest body of work, I'm doing something somewhat (6) similar because I'm repeating marks across multiple canvases. I'll be working on, let's say, four paintings simultaneously and doing the exact same painterly mark on all of them.’ Auto-plagiarism, but with a difference. What (7) should we call this? Names and titles are difficult – too abstract. To un-title (be un-titled, un-entitled) is to see ‘properly’, or rather to be seen in its own seeing. So what do we call this? ‘Commensalism’? ‘Chain-painting’? Why (8) not ‘entanglement’ (too trendy?); ‘reciprocal determination’ (too retro?); ‘interpenetration’ (toxic?); or ‘inter-pictures’, ‘chiasmic pictures’, resonance, symbiosis, endosmosis…?

Of course, there have always been ‘simultaneous layers in a painting’ – and they have always been visible, even if not necessarily seen by everyone. But Guérin’s is a temporal simultaneity – a two-for-one: perceiving the past and remembering the present (Morandi: ‘repetition…remembers its object in a forward motion’) . The ‘double life of a (9) painting’. Yet also the life-doubled of a thing. Even things have their own alter-egos and doppelgängers. Things (10) haunt themselves in their own multiple times. Painter/paint as ‘medium’ (double entendre). But their abstractions are not taken from formed things so much as quasi-things, nearly-things, objects glimpsed in their formation.

Yet is this merely a misremembered interior design for a Proustian space that never was? It is neither nostalgic nor unreal, however, so much as hyper-perceptive. Autistic overload, hermetic seeing. Bicameral painting as a new neuro-diversity, and with that, a ‘proper’ binocular looking, ‘looking into versus looking at’ (Celmins’ ‘super-looking’). A constructive interference between paintings across the same space and same time – a double (11) production, or better, the production of doubleness or ‘Twin-ness’, so that, walking around the gallery, you have always seen each painting at least once before. In the end (which never is a full resolution), it is the paintings that foreground themselves and decide for us. They show us how to look at them: as abstract ghosts adhering to each other, haunting each other, as memories of different presents immanent in what we see. Their look is no longer in the background.

Text by John Ó Maoilearca

1 Henri Bergson, Matter and Memory (Zone Books, 1988), p.145.

2 Magalie Guérin, Notes On (Green Lantern Press, 2019), pp.200, 42. My italics

3 Guérin, Notes On, p.75.

4 Michel Henry, Voir l’invisible. Sur Kandinsky (Éd. Bourin-Julliard, 1988), p.96.

5 Guérin, Notes On, p.56.

6‘Interview: Magalie Guérin’s multiple endings’ at

https://www.twocoatsofpaint.com/2019/03/interview-magalie-guerins-multiple-endings.html

7 Robert Enright, ‘The Place of Painting: Interviews with Alex Janvier, Tammi Campbell, Magalie Guérin’, in Border Crossings, vol.38 (2019), pp.121-26: p.126.

8 Guérin, Notes On, pp.201, 19.

9 Guérin, Notes On, p.50.

10 Guérin, Notes On, p.84.

11 Guérin, Notes On, pp.68, 58.